|

Horrea Galbae

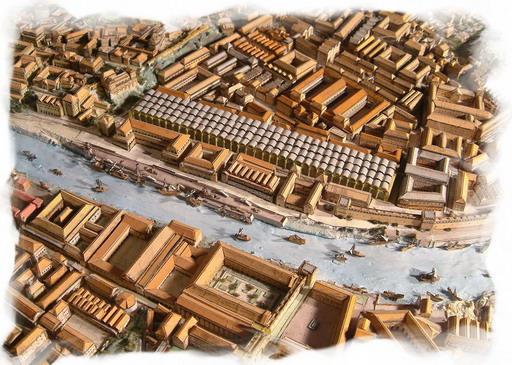

Article on pp261‑262 of Horrea Galbae: warehouses in the district known as Praedia Galbana between the south-west side of the Aventine and the Tiber. Here was the tomb of Ser. Sulpicius Galba, consul in 144 (6) or 108 B.C. (7) (CIL I2.695 = VI.31617; cf. NS 1885, 527; BC 1885, 165; Mitt. 1886, 62), and about that time, or before the end of the republic, the horrea were built and called Sulpicia (Hor. Carm. IV.12.18) or Galbae (Porphyr. ad loc.; Chron. p146; CIL VI.9801, 33743; XIV.20; cf. Galbeses, VI.30901; Galbienses, VI.710 = 30817; Not. Reg. XIII: Galbes, 33886; IG XIV.956 A.). Other forms of the name are horrea Galbana ( Not. dign. occ. IV.15 Seeck; CIL VI.338 = 30740) and Galbiana (VI.236, 30855, 33906). They were enlarged or restored by the Emperor Galba and therefore, in later times, their erection seems to have been ascribed to him (Chron. 146: (Galba) domum suum deposuit et horrea Galbae instituit (cf. CIL VI. 8680=33743 [Bonae Deae vel Tutelae] horriorum (sic) Servii Galbae Imp. Aug.). These warehouses were not only the earliest of the many in this and other parts of the city, but apparently always the most important (cf. Not. Reg. XIII; Not. dign. loc. cit.: curator horreorum Galbae), and were depots not only for grain, but for goods of all kinds (Porphyr. loc. cit.: Sulpicii Galbae horrea dicit hodieque autem Galbae horrea vino et oleo et similibus aliis referta sunt; CIL VI.980: piscatrix de horreis Galbae, 33906: sagarius; 33886: negotiator marmorarius; cf. BC 1885, 110‑112; DE III.967‑986).  These horrea came under imperial control at the beginning of the principate and provided space for the storage of the annona publica. Their staff of officials was organised in cohortes, (2) and sodalicia (CIL cit.; Gilb. III.285; BC 1885, 51‑53). In the sixteenth century excavations were made on this site (LS III.175) , and since 1880 the whole district has been laid out with new streets. During this process a large part of the walls and foundations of the horrea were uncovered. Before 1911 the principal part excavated was a rectangle on each side of the present Via Bodoni, about 200 metres long and 155 wide, enclosed by a wall and divided symmetrically into sections separated by courts. These courts, three in number, were surrounded by travertine colonnades, through which opened the chambers of the warehouses (see LF 40; BC 1885, 110‑129; LR 525‑526; HJ 175‑176) . More recent excavations (3) at various points indicate that the horrea were much larger, extending north-west beyond the present Via Giovanni Branca and as far as the river to the south-west (BC 1911, 206‑208, 246‑260; 1912, 152; 1914, 206; NS 1911, 205, 317, 340, 443; 1912, 121‑122; AA 1913, 144). The construction was mostly in opus reticulatum. Lead pipes with an inscription of Hadrian were found, and a hoard of coins (149‑268 A.D.). More recently remains of horrea were found just upstream of the new Ponte Aventino (see Emporium). The descriptions of these horrea by earlier writers, such as Benjamin of Tudela of the twelfth century (Jord. II.68) and Fabretti (de aquis, 1680, 165; RE VIII.2461) are of doubtful value, as they probably did not distinguish accurately between the horrea and surrounding buildings, like the Emporium. The remains of the 'horrea publica populi Romani' were sufficiently conspicuous to give their name to a mediaeval region; and we have records of three churches called 'in horrea'

The Authors' Notes:Cf. ib. 30855, a dedication to the Bona Dea Galbilla by a vilicus horreorum Galbianorum cohortium trium. Gatti (Mitt. 1886, 71) held that 'cohors' meant a courtyard (Italian 'corte');º cf. CIL VIII.16368; DE III.979. For still later discoveries see BC 1925, 279, 280; 1926, 267, 268.

Recourses:

|